the ultimate knowledge = the honest knowledge = truth?

On a conscious and critical level, the notion that actual ‘truth’ exists, or is a worthwhile entity for which to search for in everyday postmodernist digital society, strikes me, at first, as a pointless exercise. What possible ‘truth’ is there within the endless streams of tweets, posts and sites that are so riddled with self-promotion, spin, and often masked authorship? How does ‘truth’ online relate to any considered ‘truth’ in physical space?

We ‘all’ know that the situation of living within postmodern digital society offers endless multiple speculations, criticisms, theories. There is no complete certainty, no evidence that can be ruled out entirely as a lie, and definitely no one way of living. The notion of ‘truth’ and its necessity for living is redundant, right? Or on the other hand, is the belief of ‘truth’ embedded so deeply in our cognitive mind set and behaviour – that we seek by way of discovering information, an attempt to reveal a ‘truth’?

We are educated in institutions that often advocate the importance of truth, and the significance of uncovering the definitive information we can hold in complete certainty, closely linking this ‘ultimate knowledge’ to ‘the honest knowledge’.

For example, the University of Lancaster’s institutional motto states Patet Omnibus Veritas – ‘Truth Lies Open to All’[1]. In this dictum, the institution optimistically equates the obtainment of knowledge (achieved through exclusive higher study) to an idealised ‘truth’ which is positioned as the most desired attainment in life. At a glance, this suggestion of ‘truth’ in the universities branding, sits uncomfortably against HE pedagogy – which endeavours to promote independent, critical thinking. Instead of discovering collectively one ‘truth’, or answer accepted and practiced by all, our students should be questioning existing research and presenting their own individual lines of argument both within, and beyond education.

Patet Omnibus Veritas – ‘Truth Lies Open to All'

Similarly, the University of Glasgow presupposes on its crest “Via, Veritas, Vita”, translated in English as ‘The Way, The Truth, The Life’. This is an abbreviated version of Jesus’s statement in John (14:6) from the greatest grand narrative of all – The Bible. ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me.’ Again, pointing to ultimately, one way of being, one right and wrong, one truth and one lie. Both institutions promote critical thinking and research, however the philosophy at the core of the organisation suggest the notion of ‘truth’ being related to obtainment of knowledge through the research process. So how does uncovering information, or the truth, relate to the idea of The Truth, as in the grand narrative of ‘the truth, the way, the life’ ?

Via, Veritas, Vita” - ‘The Way, The Truth, The Life’

5292 miles to seek ‘truth’?

So, I will admit freely at the beginning of June 2011, I found myself travelling 5292 miles from London, England to Chongqing, China, to investigate the ‘truth’ relating to a certain set of circumstances.

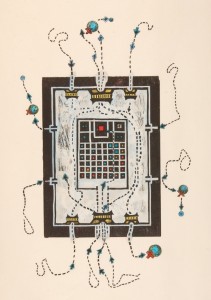

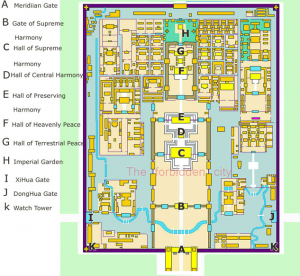

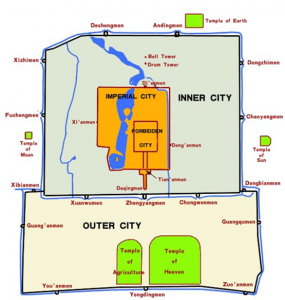

As part of a five week residency at the 501 Artspace in Chongqing, China, (funded by the Arts Council England, and supported by the Chinese Art Centre) I set out to ‘uncover the reality’ of current constraints set upon residents in the People’s Republic of China when occupying digital and physical space. Within my brief, I would research into how local inhabitants occupied present day physical and urban space, digital space, and how these experiences of control related to historical Ming Dynasty architecture and town planning. The research would inform a body of drawings, prints and installations exploring these themes.

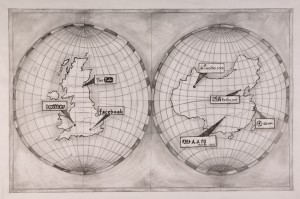

As you are more than likely aware from international media, internet users from the People’s Republic of China, cannot move freely within the supposedly libertarian internet. Numerous sites that are deemed as inappropriate, with overly sexual content, or questioning of the government and the country’s political history are inaccessible to users. Similarly, the majority of Western networking sites; Facebook, Twitter, Blogger and Posterous, are also banned to netizen’s. When encountering a banned site, the user is met with a screen that provides one of two euphemisms. The internet user is either re-directed to another safe ‘site’ or the screen flashes up with an informative page that the ‘network has timed out’. Both of these explanations, or redirections, can be classed as ‘a lie’.

When I interviewed local inhabitants regarding their experiences of ‘redirection’, the response I met was firstly, a mixture of apathetic acceptance and lack of acknowledgement of the controlled situation from the government. Secondly, another group of locals felt frustrated by hypocritical governmental power over movement in physical and digital space. The censorship does not end with Redirection and Timeout issues; there were numerous narratives of email accounts being hacked and attached items being deleted from incoming mail, particularly from abroad. Similarly, when users access and inhabit internal PRC social networking sites, such as ‘Fanfou’, ‘Renren’ (which mimic closely iconography and features of western social networking sites) any untoward comments or behaviour are removed.

Ren Ren Logo

Fanfou Page (Twitter equivalent)

Such aforementioned actions by the PRC’s government immediately appear as deceitful behaviour, functioning from a position of relentless control. From a Western position, the government is essentially lying to its inhabitants, providing false information for the reasons that occupants are demobilised or redirected. However, as my research and understanding of the culture developed, what first appeared as a clear lie and truth, did not ultimately ‘liberate’ [2] myself or research. The evident hypocrisy of the government related to, relied, and perpetuated endless social and political systems within their society. The situation was, and is, much more complex than the simple difference between a truth and a lie.

[1]

The motto is part of the longer translation from the ‘Famosa Apologia’, a medical document from the late 17th Century. It reads: “Those who were before us are not our masters but our leaders. Truth lies open to all. It is not yet anyone’s possession. Much of it is left, even for those to come.”

Lancaster University Website – ‘Origins and Growth’. http://www.lancs.ac.uk/unihistory/growth/motto.html. Accessed: 18th October 2011.

[2] Slavoj Žižek’s ‘Good Manners in the Age of WikiLeaks’, in London Review of Books, Vol.33 No.2; 20 January 2011, writes; “However, it is a mistake to assume that revealing the entirety of what has been secret will liberate us. The premise is wrong. Truth liberates, yes, but not this truth. Of course one cannot trust the facade, the official documents, but neither do we find truth in the gossip shared behind that facade. Appearance, the public face, is never simple hypocrisy.”