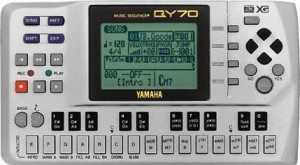

In the September 1997 issue of Sound on Sound magazine, Martin Russ described the newly released Yamaha QY70 as

“A deceptively capable workstation-like device, comprising a powerful sequencer, sophisticated auto-accompaniment and a GM/XG expander’

The QY70 was Yamaha’s most recent contribution to the line of QY models developed since 1991. The idea behind the series was to produce portable compositional tools, small bits of hardware, no larger then a paperback that would allow the amateur, enthusiast, or professional musician to compose music on the go. The QY10, Yamaha’s first release, featured the prototypical design that all subsequent models would try to update and improve on. About the size of a videocassette, the QY10 was a battery powered 8-track sequencer and crude sound generator. Being the first of its kind, the 10 sparked the development of a large number of copycat designs (including

Roland’s cumbersome Groovebox series). Yamaha cornered the market through saturation, introducing newer models that seemed to pack more and more functionality into the small box; at an almost yearly rate the QY20, 22, 300, and 700 all appeared en route to the QY70 model.

What was unique about the QY70 in 1997 was the amount of attention Yamaha paid to demystifying the creative process, or removing the blank canvas effect of having to actually think of new melodies or drum patterns. This was achieved through the customisation of a neglected feature known as auto-accompaniment (AA).

If you, or anyone in your family, has ever owned a domestic keyboard you’ll be familiar with the standard bank of about 50 song styles that you can select and play along to. The idea is that you can practice your piano playing or vocal skills without having to employ a backing band. That’s the concept of auto-accompaniment. Typical AA styles are usually dominated by musical clichés like country, 16-beat, rock, or pop styles. The options that are open to you consist of speeding up or slowing down the tempo of any one pattern, but further editing is barred. In the QY70, Yamaha not only allowed the user to isolate and edit particular tracks, you could also mix and match styles, or use them as building blocks for your own compositions. They also included a feature called Chord template. This allowed you to sift through a number of chord progressions, pre-programmed to fit musical styles like ballads, blues and Jazz. Included in this set of pre-prepared chord structures was an option titled Cliché, which, as you’d imagine, gave access to a collection of instantly clichéd chord sequences.

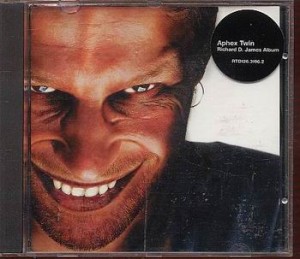

To complement these innovations in automated song generation, Yamaha included a number of unique, contemporary, AA options, including styles like Drum n Bass, Jungle and Euro Techno. They also included an option named EJ: a rather cryptic reference to a burgeoning, underground genre known as intelligent dance music – IDM for short. Possibly named after a mailing list forum created in 1993 to discuss the music of Aphex Twin and other Warp records artists, IDM was labelled intelligent because of its lineage, innovation, and compositional difficulty. Alongside Detroit techno and Chicago Acid House, IDM artists name-checked Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, Edgard Varese, Iannis Xenakis and a whole host of other composers, known for their esoteric musical output. At the forefront of this new breed of dance music producer was Richard D. James – aka Aphex Twin.

What Yamaha’s EJ preset did was reproduce and automate the stylistic flourishes and technical innovations associated with Aphex Twin’s music. Approximately one year on from the release of Aphex’s record entitled Richard D. James, Yamaha Japan charged it’s team of engineers to create an auto-accompaniment preset that would allow amateurs, enthusiasts and professionals, around the world, the chance to write like Aphex Twin. What they created was an almost exact copy, of the track entitled 4, from the Richard D James’s album.

Usually the automation of song styles is confined to what might be called traditional compositions. Stereotypical song structures we associate with genres like Country, Blues, Reggae and so on. We recognise them because they are pulled from songs that have pre-ordained structures. With IDM, or rather Aphex Twin, Yamaha’s engineers sought to copy the instantly recognisable, individual compositional style of a living artist. By placing the ability to write like Aphex in anybodies hands, they simultaneously demystified and, to an extent, neutered his artistic gesture. Not only could users play around with this tool on their portable boxes, they could transfer the midi data to their computers and use it to create compositions of releasable quality. In other words, they could feasibly profit from corporate plagiarism.

As a result, Yamaha’s quest to simplify the process of song writing, through automation, arguably contributed to the premature obsolescence of Aphex Twin’s signature style, and the particular incarnation of IDM he helped pioneer. Although IDM remains a vital genre of alternative electronic music, the increased ubiquity of Aphex’s style saw aspiring composers – and Aphex himself – retreating from it as quickly as their precursors adopted it. In the QY70’s wake software packages incorporated Aphex style features, and with each subsequent release the learning curve shortened. So, from the relative difficulty of Cycling 74’s MAX/MSP, users were able to do things at the touch of a button with Ableton Live. The casualty of this ‘democratic’ levelling of the playing field becomes the original artistic gesture.