The present returns the past to the future’ – Jorge Luis Borges

Besides prediction models based upon recovered data from the past and the present, there is nothing but imagination at hand to envision the future.

The specific interest or intent of art and all existing sciences seems to flock together whenever a distinctive humanistic evolution is inevitable, creating an épistème of knowledge [1]. In the Middle Ages we struggled to find similarities and resemblances between micro and macro, humans and god, earth and heaven. – We are all alike, mirrored by the image of God – was the prevailing dictum. It took until the 17th century before we started to look for differences, classifying species in separate models (taxonomy, Linnaeus) and paving the way for individual existence. In the 19th century Darwin and Lamarck opened the door to the past and instigated the origin of history. We discovered where we came from and started to reconstruct the string of our evolution. Marx introduced the theory of historical materialism and added why to the questions of when, where and how.

Photography was invented and gave us the first artificial tool to catch a moment. Slowly but destined we became grounded in the reality of the present.

These new certainties, knowing where we come from and the ability to define the distinctiveness of being a homo sapiens sapiens, created an outburst of self-confidence during the 20th century in art and all the other sciences, opening up endless possibilities to act within the present. The result was there, immediately visible and the responsibility was all ours. This conviction in own abilities stimulated the industrial evolution, which changed the world beyond recognition and gave way to the largest population explosion in human history. We learned to genetically manipulate life, we unravelled the mysteries of most DNA strings (including our own), we figured out a way to recreate almost anything out of almost nothing by using nanotechnology, and found ways to be

everywhere at the same time (radio, television, internet). We mastered the épistème of the present, leaving but the future to be destined.

The notion of consequence is the first manifestation of futurism; concern slowly replaced the initial euphoria about endless growth and infinite possibilities. The speed of new inventions and subsequently growing knowledge is accelerating just like the expansion of the universe and might bring us to what is currently known as the Singularity [2]. At that moment, predicted to occur around 2035, knowledge is doubled every minute, making it impossible to comprehend for ‘normal’ humans.

The Club of Rome was the first to use computer models to predict the future [3].

Some predictions proved to be farfetched since evolutions in general behave more chaotic than anticipated, but many future scenarios became reality by now. Their first report ‘Limits of Growth’ of 1972 caused a permanent interest in what is to come and it is still the best selling environmental book in world history. The second report from 1974 revised the predictions and gave a more optimistic prognosis for the future of the environment, noting that many of the factors were within human control and therefore that environmental and economic catastrophe were preventable or avoidable.

This notion of self-control in relation to making history by interfering in the present became the most important theorem of the 20th century. Also in the art world this feeling of being able to transcendent your own existence by imagining what might, what could and what should became predominant. Although a great deal of artists working with history are digging up old stories, forgotten facts and undisclosed objects of the past to reinvent and reinterpret history, a much bigger number of artists is involved in writing current history, looking at what might be relevant for future generations to remember us by. Preluded by Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol was probably the first artist to fully realize the potential of freezing and claiming history by randomly choosing an insignificant object like a can of Campbell soup or a box of Brillo soap and lifting it above oblivion. This self-proclaimed Deus Ex Machina or act of vanguardism was copied by many other artists, like Heim Steinbach, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, who, with changing luck, tried through object fetishization to declare or even force history to happen.

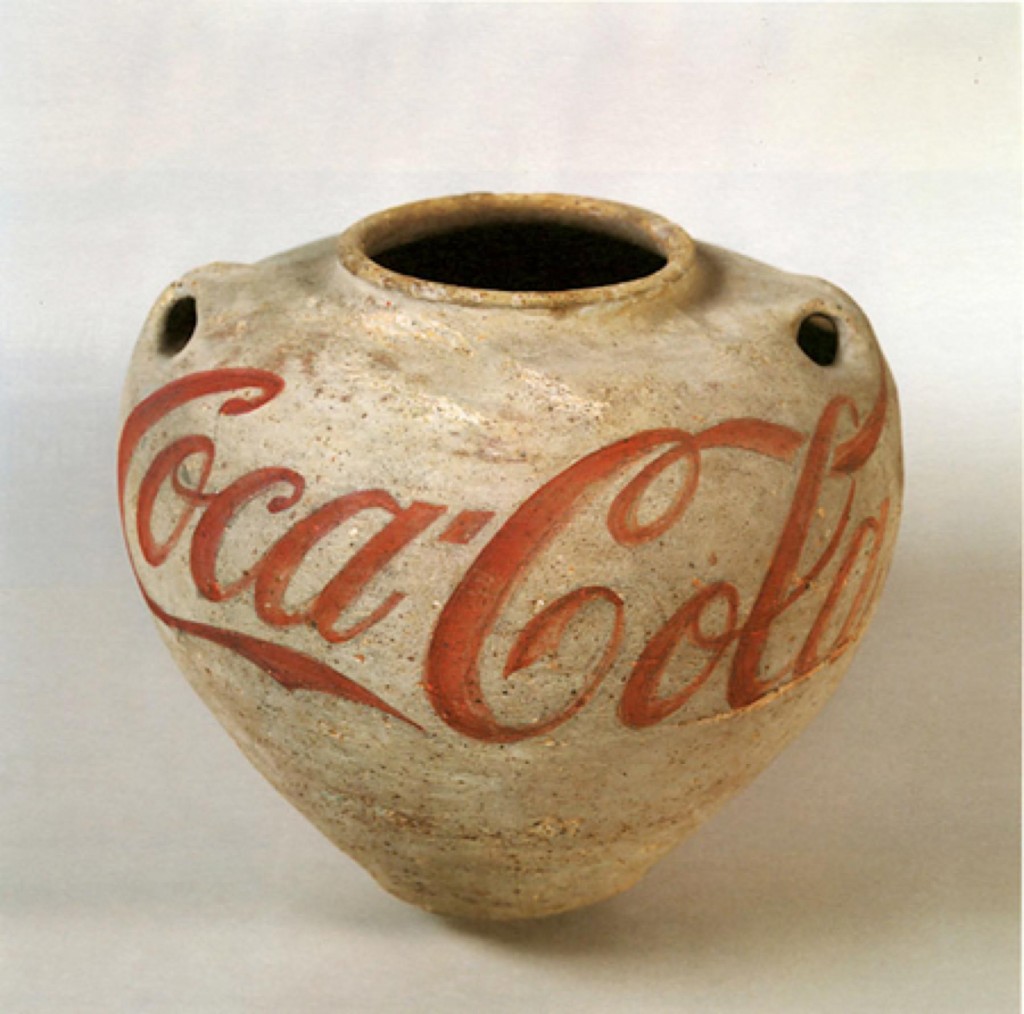

A similar strategy is the combination of elements from the past with the present, already cashing the idea that the present is also the future past and that future historians could unwillingly mingle both and by doing so creating a stimulus for an altered state of remembering or stronger; to rewrite history all together. These combined traces of different pasts create an endless chain of possible futures, visualised by artists like Simon Starling, Ai Wei Wei, Wim Delvoye and Brian Jungen.

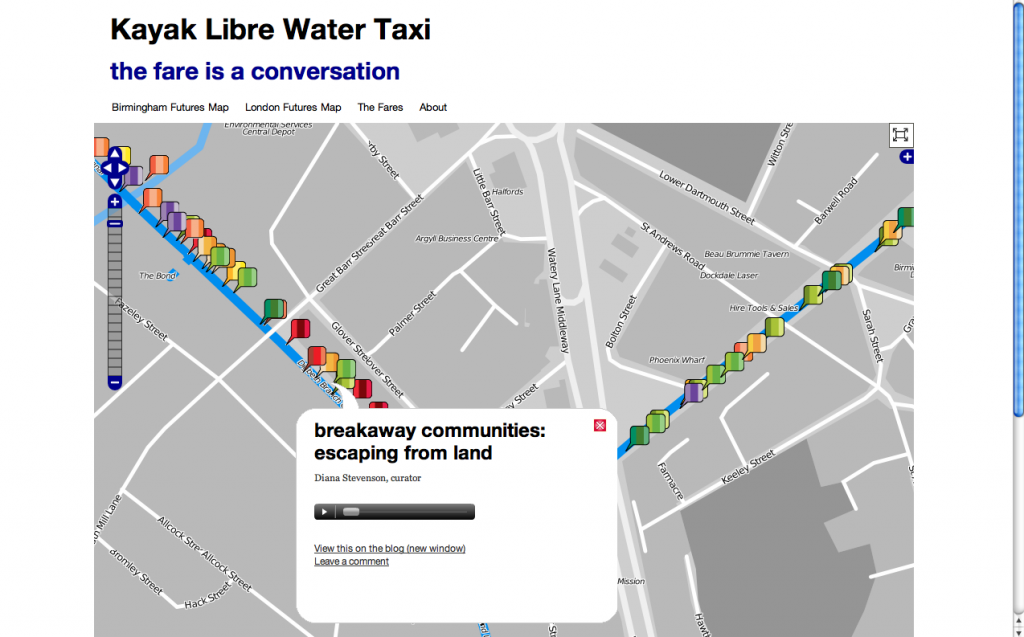

To many critics and curators focus on the past to make sense of or give value to archives, artistic research or current art production in general. By doing so, they enforce a self-fulfilling prophecy upon the work and don’t do right to the imagination and sheer curiosity of the creator towards representation of the present in the future. What will remain? What is our heritage for the future? Even artists like Gerard Richter, Roy Arden, Peter Pillar, Batia Suter and Lois Jacobs who on a first glimps seem to work with the past are rather formulating different answers to what could or should remain of the present.

Roy Arden’s Versace for instance is not looking at the past in the historical sense but merely imagining how we might look back at the past in the future. It questions the relevance or value of anything present in our contemporary society to represent that same society in the future. Many other artists like Cornelia Parker, Mark Dion, Damien Hirst and Guillaume Bijl are doing the same thing; they lay the foundation of future history. They are telling a story, our story. Cornelia Parker uses remnants of (self) destroyed parts of reality and tries to put it back together again. Mark Dion is showing the left over’s of our society in a more ‘classic’ archaeological context and Damien Hirst and Guillaume Bijl subtract a certain object or entire space out of our present world, like a slice of cake, and preserve it directly for future generations. Although using different modes of working they all work with possible remnants of our current civilisation, imagining different pieces of the puzzle that could be used in the future to puzzle back together again the history we are currently creating. They work within the future, not the past.

This interest, or calling upon, is visible not only in the current art world but across most branches of the science tree. In the field of Biology animals are duplicated, cloned, crossbred and pimped in all imaginable ways to become stronger, smaller, longer lasting, fluorescent [4], faster running,… in general better equipped for eternity. Humans haven’t only discovered how to eradicate life, destroying, willingly or not, several entire species and ecosystems in the past, by now we also know how to manipulate and maintain life. The promise of being able to cure almost any disease in the near future by using nanobots to do the dirty work, caused a real run for life extension programs like Alcor, the world leader in Cryonics [5]. More than one hundred people have been cryopreserved since the first case in 1967. More than one thousand people have made legal and financial arrangements for cryonics with one of several organizations, usually by means of affordable life insurance. The majority chose to only preserve their head, assuming that the body could be regenerated very easily in the future, using the same technique as lizards do to grow back a limb.

The current emphasis on preservation seems also in Archaeology, a science that is traditionally grounded in the past, to overrule the act of excavation. Prophesising on an eminent crisis or apocalyptic disaster inspired us to bury time capsules deep underground containing samples of current societies including their historical highlights. In 2008 the Svalbard Global Seed Vault opened its doors for all the 1,300 gene banks throughout the world. The Seed Vault functions like a safety deposit box in a bank. The Government of Norway owns the facility and the depositing gene banks own the seeds they send. The vault now contains over 20 million seeds, samples from one-third of the world’s most important food crop varieties. In 1974 Ant Farm constructed Cadillac Ranch, ten Cadillac’s, ranging from a 1949 Club Coupe to a 1963 Sedan, buried fin-up in a wheat field in Texas. Much later, in 2006, during a performance work called Burial, Paul McCarthy and Raivo Puusemp buried one of McCarty’s own sculptures in the garden of Naturalis, the National History Museum of Leiden in The Netherlands. The buried sculpture resides underground as an artefact for future discovery.

Currently, four time capsules are “buried” in space. The two Pioneer Plaques and the two Voyager Golden Records have been attached to a spacecraft for the possible benefit of space farers in the distant future. A fifth time capsule, the KEO satellite, will be launched around 2010, carrying individual messages from Earth’s inhabitants addressed to earthlings around the year 52,000, when KEO will return to Earth [6]. In Cosmology as well the focus is on the future. Experiments are conducted to create black holes, possible portals to travel through time. Terraforming attempts might create an atmosphere around a distant planet or moon creating a possible escape for human kind if planet earth is not viable anymore.

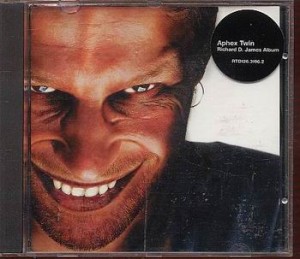

In 1971 the first artwork was placed on the moon. Fallen Astronaut, created by Belgian artist Paul Van Hoeydonck, is an aluminium sculpture of 8,5 cm representing a sexless abstraction of a human. It was left on the moon by the Apollo 15 crew next to a memorial plaque stating all the names of astronauts that died on their way to the moon. In 2003 a work of art by Damien Hirst consisting of 16 multi-coloured spots on a 5cm by 5cm aluminium plate was send to Mars. The colours would be used to adjust the camera while a special composed song of the British pop-band Blur would be played to check the sound and accompany the arrival of the Mars Lander, the Beagle 2. The sequel of Darwin’s exploration vessel was last seen heading for the red planet after separating from its European Space Agency mother ship Mars Express on December 19 2003. Part of a mission estimated to cost $85 million, the probe was supposed to land on Mars a few days later on Christmas Day and search for signs of life, but vanished without trace…

Closer to earth itself many artists have made works that can be seen from outer space. The biggest one, Reflections from Earth is made by Tom Van Sant in 1980: a series of mirrors over a 1.5 mile stretch of the Mojave Desert in the shape of an eye. In 1989 Pierre Comte did something similar with Signature Terre: sixteen squares of black plastic fabric with sides measuring 60m creating the “Planet Earth” symbol. Two noble attempts to leave a trace and write history but as a work of art not surpassing the early Land Art by Robert Smithson (Asphalt Rundown, 1969 and Spiral Jetty, 1970) or even smaller interventions by Richard Long (A line made by walking, 1967) or Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Surrounded Islands of 1980-83. No single work of art however can compete with the collaborative global effort to create a new geological layer over the earth, consisting of asphalt, concrete and plastic, contemporary materials representing our current civilisation. No matter what happens, we will all be remembered, that is for sure. We just don’t know how. Will we arrive at a moment of sufficient self-alienation where we can contemplate on our own destruction as in a static spectacle? [7]. I don’t think so. We will be too busy with self-preservation, looking back to figure out what lays ahead. Like the speakers of Aymara, an Indian language of the high Andes, who think of time differently than just about everyone else in the world, we should also position the future behind us, because you cannot see it and the past ahead of us, since that is the only thing we can see. This is precisely what so many artists are doing today; looking backwards to discover the future. Whatever lies in front of you and can be seen is used as inspiration source to imagine the unknown.

(A reaction to Dieter Roelstraete’s The Way of the Shovel: On the Archeological Imaginary in Art /e-flux journal by Maarten Vanden Eynde, April 2009)

[1] Michel Foucault used the term épistème in his work The Order of Things (Les Mots et les choses. Une archéologie des sciences humaines, 1966) to mean the historical a priori that grounds knowledge and its discourses and thus represents the condition of their possibility within a particular epoch.

[2] Ray Kurzweil, ‘The Law of Accelerating Returns’, 2001

An analysis of the history of technology shows that technological change is exponential, contrary to the common-sense ‘intuitive linear’ view. So we won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century—it will be more like 20,000 years of progress (at today’s rate). The ‘returns,’ such as chip speed and cost-effectiveness, also increase exponentially. There’s even exponential growth in the rate of exponential growth. Within a few decades, machine intelligence will surpass human intelligence, leading to the Singularity—technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history. The implications include the merger of biological and nonbiological intelligence, immortal software-based humans, and ultra-high levels of intelligence that expand outward in the universe at the speed of light.

“I would define the episteme retrospectively as the strategic apparatus which permits of separating out from among all the statements which are possible those that will be acceptable within, I won’t say a scientific theory, but a field of scientificity, and which it is possible to say are true or false. The episteme is the ‘apparatus’ which makes possible the separation, not of the true from the false, but of what may from what may not be characterised as scientific”.

[3] The Club of Rome is a global think tank that deals with a variety of international political issues. It was founded in April 1968 and raised considerable public attention in 1972 with its report Limits to Growth. In 1993, it published followup called The First Global Revolution. According to this book, “It would seem that humans need a common motivation, namely a common adversary, to organize and act together in the vacuum; such a motivation must be found to bring the divided nations together to face an outside enemy, either a real one or else one invented for the purpose….The common enemy of humanity is man….democracy is no longer well suited for the tasks ahead.”, and “In searching for a new enemy to unite us we came up with the idea that pollution, the threat of global warming, water shortages, famine and the like, would fit the bill.” This statement makes it clear that the current common adversary is the future itself.

[4] Alba, the first green fluorescent bunny made by artist Eduardo Kac in 2000, is an albino rabbit. This means that, since she has no skin pigment, under ordinary environmental conditions she is completely white with pink eyes. Alba is not green all the time. She only glows when illuminated with the correct light. When (and only when) illuminated with blue light (maximum excitation at 488 nm), she glows with a bright green light (maximum emission at 509 nm). She was created with EGFP, an enhanced version (i.e., a synthetic mutation) of the original wild-type green fluorescent gene found in the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria. EGFP gives about two orders of magnitude greater fluorescence in mammalian cells (including human cells) than the original jellyfish gene.

[5] Cryonics is the speculative practice of using cold to preserve the life of a person who can no longer be supported by ordinary medicine. The goal is to carry the person forward through time, for however many decades or centuries might be necessary, until the preservation process can be reversed, and the person restored to full health. While cryonics sounds like science fiction, there is a basis for it in real science. (www.alcor.org)

[6] KEO, The satellite that carries the hopes of the world. What reflections, what revelations do your future great grandchildren evoke in you? What would you wish to tell them about your life, your expectations, your doubts, your desires, your values, your emotions, your dreams’? (www.keo.org)

[7] Walter Benjamin (Technocalyps – Frank Theys, 2006)