The Original Notion (a)

I wanted to make a 1 million-piece jigsaw puzzle. It was a whimsical piece of work, most likely to be manufactured- and outsourced- and hopefully, quite modest.

Now, I Google the stupid idea before I make it because when I did research the idea, the results were better than my thoughts- a 600 million piece puzzle with a deeper social meaning than that I had intended to provide.

I like this humility, it’s not good for me personally- nor does it bode well for artists.

The Better Idea (b)

Reassembling a puzzle with 600 million pieces

Published On Sun Jan 20 2008

Brett Popplewell Staff Reporter

Nineteen years ago, as the Berlin Wall crumbled and democracy swept through communist East Germany, STASI agents – members of the secret police – worked feverishly to destroy millions of top-secret documents in an effort to keep them from Western eyes. Attempting to shred some 45 million items as quickly as possible, the agents fed page after page into shredding machines. The equipment quickly jammed, leaving the agents to tear up the materials by hand and throw them into garbage bags meant to be incinerated. But with East Germany quickly falling into the hands of the west, the agents were stopped before they could burn the shreds. Some 600 million pieces in 16,000 bags became the property of the current German government. They have remained, for the most part, in that state.

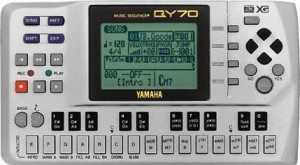

Then, in May 2007, the German government revealed the world’s most sophisticated pattern-recognition machine, the $8.5 million dollar (U.S.) E-Puzzler, which can digitally put back together even the most finely shredded papers. Developed in Berlin by the Fraunhofer Institute of Production Facilities and Construction Technology, the E-puzzler is a computerized conveyor belt that runs shards of shredded and torn paper through a digital scanner. Scanning up to 10,000 shreds at once, the machine links them together by their colour, typeface, outline, shape and texture – not unlike how the average human might try to piece together a puzzle. The machine then displays a digital image of the original document on a computer screen.

“The task to automatically reconstruct 16,250 bags full of torn documents using a technical system . . . presents an enormous technological challenge,” says Bertram Nickolay, the lead inventor of the machine.

During the Cold War, East Germany’s Ministry for State Security – STASI – was regarded as one of the most formidable secret police forces of its day. Using a vast network of civilian informants, the STASI kept files on up to 6 million of East Germany’s 16 million citizens through an estimated 400,000 informants from all walks of life. For decades, neighbours spied on neighbours, priests spied on their flocks, husbands spied on their wives and even children spied on their parents. They reported their discoveries to the 90,000 STASI agents keeping tabs on the population.

Prior to the creation of the E-puzzler, a team of 15 Germans had laboriously been putting the pieces together by hand. But they managed to rebuild only 10,000 documents from 300 bags during 12 years. The German government estimated it would take a further 600 to 800 years to finish the job. But having uncovered heartbreaking stories of espionage – like that of Vera Lengsfeld, a 54-year old German politician who was shocked to learn she had been spied on by her husband for 11 years – the German public demanded the files be put together more quickly. An estimated 3.4 million Germans have officially requested to see the information the STASI gathered on them. With the E-puzzler, Nickolay says the government will be able to un-shred the remaining documents by 2013. Nickolay acknowledges his machine’s importance in helping millions of Germans to piece together their former lives. But says his machine is even more significant to the rest of the world.

In addition to piecing together shreds of paper, the machine has been used by Chinese archaeologists to reconstruct smashed Terracotta warriors found in the tomb of Emperor Qin. And the equipment has deciphered barely-legible lists of Nazi concentration camp victims. There is only one E-puzzler in operation, but Nickolay’s team has received interest from other former Eastern Bloc countries looking for a way to get at their own state secrets of the past.

“It’s no longer safe to shred a document,” Nickolay says. “The only safe way to destroy something is by burning it.”